In the Studio with Patch Rogers

Join the Arts and Crafts antiques and restoration expert as he shows Liberty around his serene Sussex workshop

Read more

In the Studio with Patch Rogers

Join the Arts and Crafts antiques and restoration expert as he shows Liberty around his serene Sussex workshop

When one thinks of a quintessentially English vignette, they probably imagine something like the bucolic Sussex countryside that antiques expert Patch Rogers calls home. Sequestered in the unassuming, lush rolling hills of the South Downs, surrounded by dense woodland, meadows and open pasture, only a small square sign perched at the top of a dirt track offers a hint at what’s to come.

As the sun beams down on an uncharacteristically balmy spring day, Patch Roger’s modest, tumbledown barn-turned-workshop-and-studio glistens in the sunlight. Stepping through the glass doors, the surroundings hush, the temperature drops, and it’s clear that something extraordinary is afoot.

As an expert restorer specialising in the Arts and Craft period, Rogers has worked closely with Liberty for many years, with his meticulously restored discoveries gracing Liberty’s fourth floor. Many of the pieces available in Liberty were first sold in the store itself when the movement was at its height, before being recovered, revived and returned thanks to Roger’s expert eye.

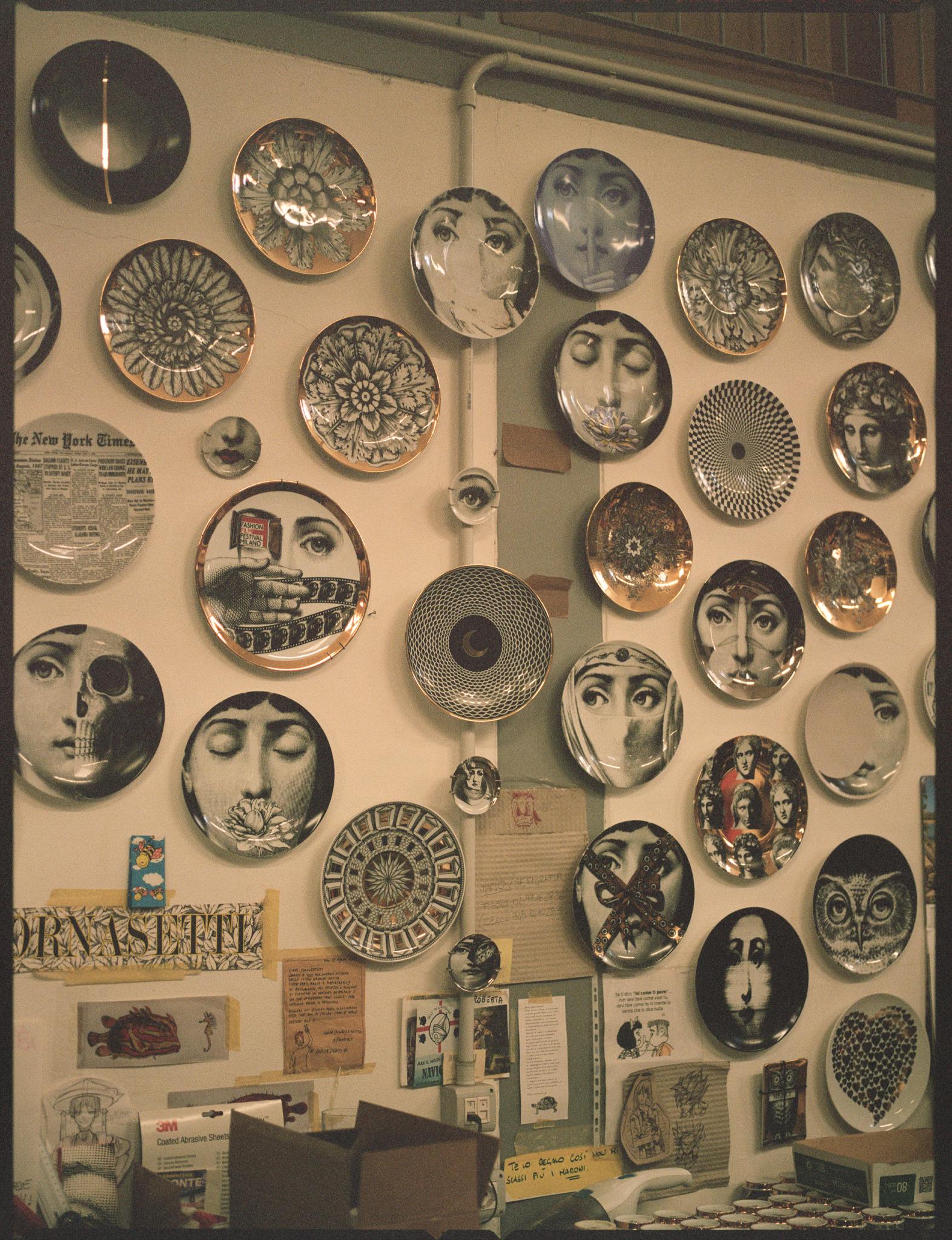

In the cool, calm surrounding of his studio, there lies a treasure trove of unique, captivating pieces of furniture, fabrics, lighting and art – each with a complex and rich history that Rogers gleefully explains piece by piece. From curvaceous Thebes stools, to towering wardrobes, and sinuous chairs, every corner feels remarkable.

In the other half of the old barn, is the workshop – where pieces in progress wait to be restored to their former glory. This, according to Rogers, is where he is most at home, describing artful restoration as the “unsung hero”.

As a fresh selection of Arts and Crafts pieces from the Patch Rogers studio make their way to Liberty to be displayed in store as part of our 150th anniversary – he shared his own journey into the antiques world, and gave a glimpse into Liberty’s Arts and Crafts legacy.

When did you first become interested in antiques?

Straight from school, really. It was one of those things where I fell into it, and then never got out of it - but it's something I love, so that's not a problem! It wasn't something that was in the family or anything like that, I just found a job and I loved it.

Do you remember the first thing that you acquired?

The first thing I ever fell in love with was a chest of drawers. I was told the story of this piece, made by a company called Brynmawr Furniture Company. In the 1930s, during the depression, it was a mining community in South Wales. The wealthy mine owner felt guilty as, because of the depression, everyone was unemployed, all the miners went without money and food. So, he taught them all to make furniture.

It suddenly it just clicked. For me, that then gave me an interest in this period and that's kind of what this is about: it's about socialism, looking after the craftsmen, looking after the workers, and a reaction against all those excesses of Victorian indulgence.

You specialise in the Arts and Crafts period – what would you say are the notable elements of the movement?

The Arts and Crafts period really started around 1880 to 1885. The term itself was coined by Walter Crane, who also designed fabrics for Liberty. It was a reaction against poor design and mass production during the Victorian period. A group of architects and designers collaborated with makers to create beautiful things that were, at the time, quite reactionary.

It is important to remember that when a designer created something back then, they designed everything – fabrics, furniture, the house, even the electric light switches. Everything in a house would be part of their vision. For me, although I mostly deal in furniture, it is the completeness of that vision that makes it so interesting. There is lighting, fabrics – everything to do with the home. That cohesive approach makes sense to me.

How does Liberty fit into the Arts and Crafts movement?

The movement began around with A. W. N. Pugin, who designed the interiors for the Palace of Westminster. Then William Morris took hold of the ethos in the late Victorian period, designing and making furniture, textiles, and more.

Retailers in London began to take notice around the 1870s, and Arthur Lasenby Liberty saw an opportunity and opened his store on Regent Street. Initially, he focused on Oriental design and imported furniture from abroad. But by the 1880s, Liberty was designing and making Arts and Crafts furniture in-house, with their own designers and workshops. It became hugely popular.

You mentioned being located the countryside and how that's connected to the Arts and Crafts ethos. How so?

I am very much about the workshop. There is no better place to do that than surrounded by nature – it is where the movement drew much of its design inspiration. Nature, flora and fauna – it is all there. I have worked in cities, but having nature around definitely helps.

What is your process when restoring furniture?

It's all about vision. Sometimes, pieces arrive in poor condition – painted over, for example. I once had a William Morris settle that originally had been ebony black, but had been painted with Annie Sloan [chalk] paint. It took two painstaking weeks to strip it, but the result was beautiful.

You need to know what it should look like, and that comes from having seen a lot of furniture. In restoration, less is always more. It is the unsung hero – you should not see the restoration. If it looks fresh and natural, like it has always been that way, that is the goal.

Do you have any current favourite pieces in the barn? Or ones that are long gone but unforgettable?

So many. The worst is looking through old photos and realising I will never have some of those pieces again. There was a wardrobe designed by M. H. Baillie Scott, an important Arts and Crafts architect. It came to me painted white and in pieces. We restored it, recreated the original paint, redid the metalwork, and it looked incredible. It ended up in a museum in Sicily.

Have you restored other pieces that have ended up in museums?

Years ago, we had runners who would travel the country going to auctions. One rang me from a phone box about four Baillie Scott pieces. We bought two and another dealer bought the other two. They had never been seen on the market before. One of ours, a bureau, is now at Blackwell House in Windermere. The other, a three-legged table, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. That is quite something.

Why is it important for Liberty to maintain a connection to the movement?

It is extraordinary that a 150-year-old store can have original furniture come back in and be resold again. That kind of provenance does not happen elsewhere. It is part of Liberty’s history and fits well alongside modern styles – 1950s, mid-century, whatever. The right pieces hold their own in terms of design. That is why they work, even mixed with modern fabric.

Is there a ‘Holy Grail’ item you would love to find one day?

I’m fortunate to have already had the chance to handle pieces by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, which I never thought possible. But there is a chair by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo, a forerunner of Art Nouveau, that is incredibly significant. This is the chair that broke the mould that got everyone interested. Only a few exist and they are all in museums now. The last ones sold for over £200,000, but they were originally found for next to nothing. That is what I would love to find – something that looks like just a chair until you have the knowledge that turns out to be the chair.

So, it could be sitting in someone’s garage right now?

Absolutely. In someone’s garage or shed – it is out there somewhere.

Discover Patch Rogers's antiques in store at Liberty, and see a selection of his Arts and Crafts pieces on the Fourth Floor.